As previously stated I was with Blenker’s brigade of Miles’s division, the duty of which was to guard Blackburn’s and other fords. Early on the forenoon of the 21st (July) I took post on a prominent knoll overlooking the valley of Bull Run. Here I remained in readiness to move my battery quickly to any point where its service might be required. Stretched out before me was a beautiful prospect. To the south, directly in front of me, distance about five miles, was Manassas Junction, where we could perceive trains arriving and departing. Those coming from the direction of Manassas were carrying Johnston’s troops from the Shenandoah. Around towards our right was the Sudley Springs country, nearing which the turning column now was. All the country in that direction appeared from our point of view, to be a dense forest, and a good of it was in woods, the foliage and buildings only were discernible. Among these were the Robinson and Henry houses, and the fields upon the plateau soon to become famous in history as the scene of deadly strife. Still further around to our right and rear, distant about a mile was Centreville, a mere village of the “Old Virginny” type. Through it ran the old dilapidated turnpike from Alexandria to Warrenton. By this road soon commenced to arrive a throng of sightseers from Washington. They came in all manner of ways, some in stylish carriages, others in city hacks, and still others in buggies, on horseback and even on foot. Apparently everything in the shape of vehicles in and around Washington had been pressed into service for the occasion. It was Sunday and everybody seemed to have taken a general holiday; that is all the male population, for I saw none of the other sex there, except a few huxter women who had driven out in carts loaded wit pies and other edibles. All manner of people were represented in this crowd, from most grave and noble senators to hotel waiters. As they approached the projecting knoll on which I was posted seemed to them an eligible point of view, and to it they came in throngs, leaving their carriages along side of the road with the horses hitched to the worm fence at either side, When all available space along the road was occupied they drove into the vacant fields behind me and hitched their horses to the bushes with which it was in a measure overgrown. As a rule, they made directly for my battery, eagerly scanning the country before them from which now came the roar of artillery and from which could occasionally be heard the faint rattle of musketry. White smoke rising here and there showing distinctly against the dark green foliage, indicated the spot where the battle was in progress. I was plied with questions innumerably. To those with whom I thought it worth while I explained, so far as I could, the plan of the operation then in progress. But invariably I was asked why I was posted where I was, and why I was not around where the fighting was going on. To all of which I could only reply that the plan of the battle required that we should guard the left until the proper time came for us to engage. To make my explanation more lucid I said if the enemy were allowed freedom to break through here where would you all be. Most of the sightseers were evidently disappointed at that they saw, or rather did not see. They no doubt expected to see a battle as represented in pictures; the opposing lines drawn up as on parade with horsemen galloping hither and thither, and probably expecting to see something of the sort by a nearer view of the field they hurried on in the direction of the sound of battle, leaving their carriages by the roadside or in the fields. These were the people that made such a panic at the Cub Run bridge.

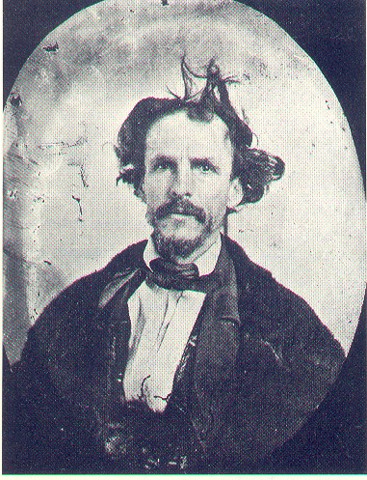

Among those who thus halted a little while with me were several that I knew. One party in particular attracted my attention. This was Dr. Nichols, then in charge of the government Insane Asylum; Senator Wilson from Massachusetts, Chairman of the Senate Military Committee; “Old Ben” Wade, Senator from Ohio, and a wheel horse of the Republican part; and “Old Jim” Lane, senator from Kansas, and another political war horse. All of these were full of the “On to Richmond” fever, and were impatient to see more of the battle. I endeavored to dissuade them from proceeding further, that if they would only remain awhile they would probably see as much of it as they would care to see. But Old Jim was firey, he said he must have a hand in it himself. His friends not wishing to go so far as that tried to convince him that he could do no good in the fight without a gun. “O never mind that,” he said, “I can easily find a musket on the field. I have been there before and know that guns are easily found where fighting is going on. I have been there before and know what it is.” He had been colonel of an Indiana regimt during the Mexican ware, and this was the old war fire sparkling out again. Nothing could hold him back and off the parted started down the slope and over the fields in the direction of the firing. I saw nothing more of them until late in the afternoon.

About 4. P. M. an aid (Major Wadsworth) came hurredly to me with instructions from General McDowell, to hasten with my battery down the turnpike towards the Stone Bridge. I supposed this was simply in accordance with the developments of the battle, and that the turning movemt had now progressed so far that we could now cross over and take part in it. To get on the turnpike I had to go through Centreville, where I saw Colonel Miles, our division commander, airing himself on the porch of the village inn. By this time the road was pretty well crowded with ambulances carrying the wounded, and other vehicles, all hurredly pressing to the rear. Miles, evidently in ignorance of what was transpiring at the front, asked me what was up. I could only answer that I had been ordered to proceed down towards the Stone Bridge; and then I proceeded, but the farther I proceeded the thicker the throng because of wagons, ambulances and other vehicles. The road being cut on the side of a hill had a steep bank up on its left and a steep bank down on the left, so that I could not take to the fields on either side. My horses were scraped and jammed by the vehicles struggling to pass me in the opposite direction. As far as I could see ahead the road was crowded in like manner. Finally it became impossible for me to gain another inch, and while standing waiting for a thinning out of the struggling mass, a man came riding up towards me, inquiring excitedly, “whose battery is this.” I told him that I commanded it. “Reverse it immediately and get out of here, I have orders from General McDowell to clear this road” and added that the army had been ignominiously and was now retreating. He was curious, wild looking individual. Although the day was oppressively hot he had on an overcoat – evidently a soldier’s overcoat dyed a brownish black. On his head he wore a soft felt hat the broad brim of which flopped up and down at each of his energetic motions. But notwithstanding the broadness of the brim it did not protect his face from sunburn, and his nose was red and peeling from the effects of it. He had no signs of an officer about him and I would have taken him for an orderly had he not had with him a handsome young officer whom I subsequently came well acquainted with, as Lieutenant afterwards Colonel Audenried. Seeing this young officer was acquainted with my lieutenant, afterwards General Webb, of Gettysburg game, I sidled up to them and inquired of him who the stranger was giving me such peremptory orders. He told me that he was Colonel Sherman, to whom I now turned and begged him pardon for not recognizing him before. I told him what my orders were, but he said it made no difference, the road must be cleared, and added that I could do no good if I were up at the Stone Bridge. I then reversed my battery by unlimbering the carriages, and after proceeding a short distance to the rear, where the bank was less steep, turned out into the field, where I put my guns in position on a knoll overlooking the valley towards Cun Run. In the distance I could see a line of skirmishers from which proceeded occasional puffs of smoke. This was Sykes’ battalion of regulars covering the rear.

I had not been in this position long before I saw three of my friends of the forenoon, Wilson, Wade and Lane, hurrying through the field up the slope toward me. Dr. Nichols was not now part of the party. Being younger and more active than the others he had probably outstripped them in the race. Lane was the first to pass me; he was mounted horsebacked on an old flea-bitten gray horse with rusty harness on, taken probably from some of the huxter wagons that had crowded to the front. Across the harness lay his coat, and on it was a musket which, sure enough, he had found, and for ought I know may have done valorous deeds with it before starting back in the panic. He was long, slender and hay-seed looking. His long legs kept kicking far back to the rear to urge his old beast to greater speed. And so he sped on.

Next came Wilson, hot and red in the face from exertion. When young he had been of athletic shape but was now rather stout for up-hill running. He too was in his shirt sleeves, carrying his coat on his arm. When he reached my battery he halted for a moment, looked back and mopping the perspiration from his face exclaimed, “Cowards! Why don’t they turn and beat back the scoundrels?” I tried to get from him some points of what had taken place across the Run, but he was too short of breath to say much, Seeing Wade was toiling wearily up the hill he halloed to him, “Hurry up, Ben, hurry up”, and then without waiting for “Old Ben” he hurried on with a pace renewed by the few moments of breathing spell he had enjoyed.

Then came Wade who, considerably the senior of his comrades, had fallen some distance behind. The heat and fatigue he was undergoing brought palor to his countenance instead of color as in the case of Wilson. He was trailing his coat on the ground as though too much exhausted to carry it. As he approached me I thought I had never beheld so sorrowful a countenance. His face, naturally long, was still more lengthened by the weight of his heavy under-jaws, so heavy that it seemed to overtax his exhausted strength to keep his mouth shut, I advised him to rest himself for a few minutes, and gave him a drink of whiskey from a remnant I was saving for an emergency. Refreshed by this he pushed on. Of these three Senators two, Wade and Wilson, became Vice Presidents of the United States, while the third, Lane, committed suicide, ad did also, before him, his brother, an officer in the army, who in Florida, threw himself on the point of his sword in the Roman fashion. One of the statesmen who had come out to see the sights, a Mr [Ely], a Representative in Congress from [New York], was captured and held in [duress?] vile as a hostage to force the liberation of certain Confederates then held by the United States governmt.

Among the notables who passed through my battery was W. H. Russell, L.L.D. the war correspondent of the London Times. He was considered an expert on war matters through his reports to the Times during the Crimean war and subsequently from India during the Sepoy mutiny. Of average stature he was in build the exact image of the caricatures which we see of John Bull – short of legs and stout of body, with a round chubby face flanked on either side with the muttin chop whiskers. His, like all others, was dusty and sweaty but, notwithstanding, was making good time, yet no so fast that his quick eye failed to note my battery, which he described in his report as looking cool and unexcited. He bounded on like a young steer – as John Bull he was, but while clambering over an old worm fence in his path the top rail broke, pitching him among the brambles and bushes on the farther side. His report of the battle was graphic and full, but so uncomplimentary to the volunteers that they dubbed him Bull Run Russell.

Each of the picknickers as they got back to where the carriages had been left took the first one at hand, or the last if he had his wits about him enough to make a choice. This jumping into the carriages, off they drove so fast as lash and oaths could make their horses go. Carriages collided tearing away wheels or stuck fast upon saplings by the road-side. Then the horses were cut loose and used for saddle purposes, but without the saddles. A rumor was rife that the enemy had a body of savage horsemen, known as the Black Horse Cavalry, which every man now thought was at their heels; and with this terrible vision before them of these men in buckram behind them they made the best possible speed to put the broad Potomac between themselves and their supposed pursuers.

Learning that McDowell had arrived from the field and was endeavoring to form a line of troops left at Centreville (and which were in good condition) upon which the disorganized troops could be rallied, I moved my battery over to the left where I found Richardson had formed his brigade into a large hollow square. A few months later on I don’t think he would have done so silly a thing. McDowell was present and so was Miles, who was giving some orders to Richardson. For some reason these orders were displeasing to Richardson, and hot words ensued between him and Miles, ending, finally, in Richardson saying “I will not obey your orders sir. You are drunk sir.” The scene, to say the least of it, was an unpleasant one, occurring as it when we expected to be attacked at any moment by the exultant enemy. Miles turned pitifully to McDowell as though he expected him to rebuke Richardson, but as McDOwell said nothing he rode away crestfallen and silent.

Miles did look a little curious and probably did have a we dropie in the eye, but his chief queerness arose from the fact that he wore two hats – straw hats, on over the other. This custom, not an uncommon one in very hot climates he had probably acquired when serving in Arizona, and certainly the weather of this campaign was hot enough to justify the adoption of any custom. The moral of all this is that people going to the war should not indulge in the luxury of two hats.

What Richardson expected to accomplish with his hollow square was beyond my military knowledge. He affected to be something of a tactician and this was probably only and effervescence of this affectation. Looking alternately at the hollow square and the two hats it would have been difficult for any unprejudiced person to decide which was the strongest evidence of tipsiness. A court of inquiry subsequently held upon the matter was unable to decide the question.

Richardson, formerly an officer of the 3d. infantry of the “Old” army, was a gallant fighter. He was mortally wounded at Antietam. Miles was killed at Harper’s Ferry the day before Antietam, and his name had gone into history loaded with opprobrium because of few minutes before his death he caused the white flag of surrender to be hung out. He was neither a coward nor a traitor, but too strict a constructionist of one of General Halleck’s silly orders.

Miles’s division together with Richardson’s brigade, and Sykes battalion of regulars, and four regular batteries and sever fragments of batteries made a strong nucleus for a new line on the heights of Centreville, but the demoralized troops drifted by as though they had no more interest in the campaign. And as there were again no rations it became necessary for even the troops not yet demoralized to withdraw.

A rear guard was formed of Richardson’s and Blenker’s brigade with Hunt’s and my batteries, which, after seeing the field clear of stragglers, took up the line of march at about two o’clock of the morning of July 22d, (1861) The march back was without incident so far as being pursued was concerned. For some distance the road was blocked with wrecked carriages, and wagons from which the horses had been taken. These obstructions had to be cleared away, and it was not until sometime after daylight that we reached Fairfax Court House. This village the hungry soldiers had ransacked for provisions, and as we came up some cavalrymen were making merry over the contents of a store. Seizing the loose end of a bolt of calico or other stuff they rode off at full speed allowing it to unroll and flow behind as a long stream.

The Fire Zouaves were into all the deviltry going on; they had been educated to it in New York. The showiness of their uniforms made them conspicuous as they swarmed over the county, and although less than a thousand strong they seemed three times that number, so ubiquitous were they. Although they had not been very terrifying to the enemy on the battlefield they proved themselves a terror to th citizens of Washington when they arrived there.

The first of the fugitives reached Long Bridge about daybreak on the 22d. Including the turning march around by Sudley Spring and back again this made a march of 45 miles in 36 hours, besides heavy fighting from about 10 A.M. until 4 P.M. on that hot July day – certainly a very good showing for unseasoned men, proving that they had endurance and only lacked the magic of discipline to make of them excellent soldiers. Many of them upon starting out on the campaign had left their camps standing, and thither they repaired as to a temporary home where they could refresh themselves with rations, rest and a change of clothing. This was a temptation that even more seasoned soldiers could scarcely have withstood. It was a misfortune that the battle had to take place so near Washington. More than anything else this was the reason why the demoralized troops could not be rallied at Centreville.

John C. Tidball Papers, U. S. Military Academy

Contributed by John J. Hennessy

Recent Comments