I believe that Garland found Captain Lay with a part of the Powhatan Troop at Manassas – certainly the place had been picketed for a few weeks – but that was all. Its strategic importance seemed to have been overlooked. On my arrival I found the boys comfortably quartered in tents and enjoying the contents of boxes of good things, which already had begun coming from home. In a little store at the station they had discovered a lot of delicious cherry brandy, which they were dispatching with thoughtless haste. Rigid military rule was not yet enforced, and the boys had a good time. I saw no fun in it. The battalion drill bore heavily upon me; Garland constantly forgot to give the order to shift our guns from a shoulder to a support. This gave me great pain, made me very mad, and threw me into a perspiration, which, owing to my feeble circulation, was easily checked by the cold breeze from the Bull Run Mountain, and thereby put me in jeopardy of pneumonia. Moreover, I longed for my night-shirt and the clean bed at Gordonsville. The situation was another source of trouble to me. After brooding over it a good while I got my friend Latham to write, at my dictation, a letter to John M. Daniel’s paper, the Richmond Examiner. The letter was not printed, but handed to General Lee, and additional troops began to come rapidly – one or two South Carolina regiments, the First Virginia Regiment, Captain Shields’s company of Richmond Howitzers, Latham’s Lynchburg Battery, in all of which, except the regiments from South Carolina, we had hosts of friends. The more men the sicker I got, and the further removed from that solitude which was the delight of my life. I made up my mind not to desert, but to get killed at the first opportunity. I might get a clean shirt, and would certainly get, in the grave, all the solitude I wanted.

Beauregard soon took command. This was a comfort to us all. We felt safe. About this time, too, the wives and sisters of a number of officers came from Lynchburg on a visit to the camp. That was great joy to us all. Lieutenant Latham’s little son, barely two years old, and dressed in full Rifle Grey uniform, was the lion of the hour. The ladies looked lovely. Such a relief after a surfeit of men; our eyes fairly feasted on them. Other ladies put in an appearance from time to time. Returning from Bristoe, where I had gone to bathe, my eyes fell on three of the most beautiful human beings they had ever beheld. Beautiful at any time and place, they were now inexpressibly so by reason of the fact that women were such a rarity in camp. They were bright figures on a background of many thousand dingy, not to say dirty, men. If I go to heaven – I hope I may – the angels themselves will hardly look more lovely than those young ladies did that solitary afternoon. I was most anxious to know their names. They were the Misses Carey – Hetty and Jennie Carey, of Baltimore, and Constance, their cousin, of Alexandria. No man can form an idea of the rapture which the sight of a woman will bring him until he absents himself from the sex for a long time. He can then perfectly understand the story about the ecstatic dance in which some California miners indulged when they unexpectedly came upon an old straw bonnet in the road. Pretty women head the list of earthly delights.

Over and over I heard the order read at dress parade, all closing with the formula, “By command of General Beauregard, Thomas Jordan, A. A. G.” This went on for some weeks without attracting any special attention on my part. At last some one said in my hearing: “Beauregard’s adjutant is a Virginian.” I pricked up my ears. “Wonder if he can be the Captain Jordan I knew in Washington? I’ll go and see,” I said to myself. Colonel, afterward General, Jordan received me most cordially, dirty private though I was. He was, as usual, very busy. “Sit down a minute. I want presently to have a little talk with you.” My prophetic soul told me something good was coming, and, when, after some preliminary talk about unimportant matters, he said: “So you are a ‘high private in the rear rank?'”

“Yes,” was my reply.

“Aren’t you tired of drilling?”

“Tired to death.”

“Well, you are the very man I want. Certain letters and papers have to be written in this office which ought to be done by a man of literary training, and you are just that person. I’ll have you detailed at once, and you must report here in the morning. Excuse me now, I am very busy.” Indeed, he was the busiest man I almost ever saw, and to-day in the office of the Mining Record, of New York, he is as busy as ever. A more indefatigable worker than General Thomas Jordan it would be hard, if not impossible, to find.

My duties at first were very light. I ate and slept in camp as before, reported at my leisure every morning at head-quarters, and did any writing that was required of me, General Jordan’s clerks being fully competent to do the great bulk of the work in his office. The principal of these clerks was quite a young man, seventeen or eighteen, perhaps, and was named Smith – Clifton Smith, of Alexandria, Va. – and a most assiduous and faithful youth he was. He is now a prosperous broker in New York. After midnight Jordan was a perfect owl; there were always papers and letters of a particular character, in the preparation of which I could be of service. We got through with them generally by one A.m., then had a little chat, sometimes, though not often, a glass of whiskey and water, and then I went back to camp, a quarter of a mile off, not without risking my life at the hands of a succession of untrained pickets. At camp things were comparatively comfortable. The weather was so warm that most of the men preferred to sleep out-doors on the ground. I often had a tent to myself. Troops continued to come. Many went by to Johnston (who, to our dismay, had fallen back from Harper’s Ferry), but many stayed. Water began to fail, wells in profusion were dug, but without much avail, and water had to be brought by rail. Excellent it was. Boxes of provisions continued to come in diminishing numbers, but upon the whole we lived tolerably well. The Eleventh Virginia, its quota now filled, had gone out on one or two little expeditions without material results. It formed part of Longstreet’s Brigade, and made a fine appearance and most favorable impression in the first brigade drill that took place. How thankful I was that I was not in it!

During these days when the camp of the Eleventh Virginia was comparatively deserted, the men being detailed at various duties, there occurred an episode which will never be forgotten by those who witnessed it. Coming down from head-quarters about one o’clock to get my dinner, I became aware as soon as I drew nigh our tents that something unusual was “toward,” as Carlyle would say. Sure enough there was. In addition to the ladies from Lynchburg, heretofore mentioned, we had been visited by quite a number of the leading men of that city, who came to look after their sons and wards. Several ministers, among them the Rev. Jacob D. Mitchell, had come to preach for us. But now there was a visitor of a different stripe. The moment I got within hailing distance of the captain’s tent I heard a loud hearty voice call me by my first name.

“Hello! George, what’ll you have? Free bar. Got every liquor you can name. Call for what you please.”

Looking up, I beheld the bulky form, the duskyred cheeks and sparkling black eyes of Major Daniel Warwick, a Baltimore merchant, formerly of Lynchburg, who had come to share the fortune, good or ill, of his native State. He was the prince of good fellows, a bon vivant in the fullest sense of the term, a Falstaff in form and in love of fun. What he said was literally true, or nearly so; he had all sorts of liquors. In order to test him I called for a bottle of London stout.

“Sam, you scoundrel! fetch out that stout.

How’ll you have it – plain? Better let me make you a porteree this hot day.”

“Very good; make it a porteree.”

He was standing behind an improvised bar of barrels and planks, set forth with decanters, bottles, glasses, lemons, oranges, and pineapples, with his boy Sam as his assistant. The porteree, which was but one of many that I enjoyed during the major’s stay, was followed by a royal dinner, contributed almost wholly by the major. This was kept up for a week or ten days, officers and men of the Lynchburg companies and invited guests, some of them quite distinguished, all joining in the prolonged feast, which must have cost the major many hundreds of dollars.

The major’s inexhaustible wit and humor, his quaint observations on everything he saw, his sanguine predictions about the war, and his odd behavior throughout, were as much of a feast as his eatables and drinkables. He was the greatest favorite imaginable. Everything was done to please him and make him comfortable, including a tent fitted up for him. Being much fatigued by his first day’s experience as an open barkeeper, he went to bed early, the boys all keeping quiet to insure his sleeping. Within twenty minutes they heard him snoring, and the next thing they knew the tent burst wide open and out rushed the corpulent major, clad only in his shirt, and as he came he shouted at the pitch of his stentorian voice: “Gi’ me a’r, gi’ me a’r! For God’s sake, gi’ me a’r!” Of course there was a universal burst of laughter, which the major bore with perfect good nature. Thenceforth he slept on a blanket under the canopy of heaven, enjoying it as much, he declared, as a deer hunt in the wilds of western Virginia. He carried with him, when he left, the Godspeed of hundreds of hearts grateful for the abundant and unexpected happiness he had brought them.

This was that same major who cut up such pranks in New York City a few months after the war ended – picking up a strong negro on the street and forcing him to eat breakfast with him at the Prescott House, imperiously ordering the white waiters to attend to his every want, then walking arm in arm with the negro down Broadway, each having in his mouth the longest cigar that could be bought, and puffing away at a great rate, to the intense disgust of the passers-by. Of this freak I was myself eye-witness. In the restaurants he would burst out with a lot of Confederate songs, and keep them up till scowls and oaths gave him to understand that it would be dangerous to continue, when he would suddenly whip off into some intensely loyal air, leaving his auditors in doubt whether he was Union or secesh, or simply a crank. In the street-cars and omnibuses he would ostentatiously stand up for negro women as they entered, deposit their fare, gallantly help them in and out, taking off his hat as he did, and bitterly inveighing against those who refused to follow his example. So pointed were his insults that his huge size alone saved him from many a knockdown. He lived too merrily to live long, and died in Baltimore in 1867, I believe.

Ever since the fall of Sumter Beauregard’s star had been in the ascendant. His poetical name seemed to carry a magical charm with it. Jordan had implicit faith in him. Many others looked upon him as likely to be the foremost military figure of the war, and were prepared to attach themselves to his fortunes. Keeping my place as a private detailed for duty in the adjutant’s office, I contented myself with a simple introduction to the general, and did not presume to enter into conversation with him – a privilege most editors would have claimed. (I was then editor of the Southern Literary Messenger.) But I availed myself of my opportunity to study this prominent character in the pending struggle. His athletic figure, the leonine formation of his head, his large, dark-brown eyes and his broad, low forehead indicated courage and capacity. Of his mental caliber I could not judge, but others spoke highly of it. He indefatigably studied the country around Manassas, riding out every day with the engineer officers and members of his staff. He was eminently polite, patient, and good-natured. I never knew him to lose his temper but once, and then the occasion was ludicrous in the extreme.

Just before the battle of Manassas the militia of all the adjoining counties were called out in utmost haste to swell our numbers. A colonel of one of the militia regiments, arrayed in old-style cocked hat and big epaulets, came up a morning or two before the battle and asked to see the general. When General Beauregard appeared, he said with utmost sincerity:

“General Beauregard, my men are mostly men of families. They left home in a hurry, without enough coffee-pots, frying-pans, and blankets, and they would like, sir, to go back for a few days to get these things and to compose their minds, which is oneasy about their families, their craps, and many other things.”

Beauregard’s eyes flashed fire.

“Do you see that sun, sir?” pointing to it.

“Yes, sir,” said the colonel, in wondering timidity.

“Well, sir, I might as well attempt to pull down that sun from heaven as to allow your men to return home at a critical moment like this. Go tell your men to prepare for battle at any instant. There is no telling when it may come.”

The colonel retreated in confusion.

Beauregard’s high qualities as an engineer—most signally proved by his subsequent defence of Charleston, compared with which the reduction of Sumter was a trifle—were acknowledged on all hands. What he would be at the head of an army in the open field remained to be seen. It was a trying time for him; but if he were nervous no one discovered it.

His staff was composed mostly of young South Carolinians of good family, and he had in addition a number of volunteer aids, all of them men of distinction. Ex-Governor James Chestnut was one, I think. William Porcher Miles, an accomplished scholar and elegant gentleman, I am sure was. So was that grand specimen of manhood, Colonel John S. Preston; also, Ex-Governor Manning, a most charming and agreeable companion. His juleps, made of his own dark brandy and served at mid-day in a large bucket, in lieu of something better, greatly endeared him to us all. One day all these distinguished gentlemen suddenly disappeared. Colonel Jordan simply said they had gone to Richmond; but evidently something was in the wind. What could it be? On their return, after a week’s absence, as well as I remember, there was an ominous hush about the whole proceeding. Nobody had anything to say, but there was a graver, less happy atmosphere at head-quarters. Gradually it leaked out that Mr. Davis had rejected Beauregard’s proposal that Johnston should suddenly join him and the two should attack McDowell unawares and unprepared. The mere refusal could not have caused so much feeling at head-quarters. There must have been aggravating circumstances, but what they were I never learned. All I could get from Colonel Jordan was a lifting of the eyebrows, and “Mr. Davis is a peculiar man. He thinks he knows more than everybody else combined.”

What! want of confidence in our president, at this early stage of the game? Impossible! A vague alarm filled me. I had been the first – the very first, I believe – to nominate Mr. Davis for the presidency; had violated the traditions of the oldest Southern literary journal in doing so. I had no personal knowledge of his fitness for the position. No. But his record as a soldier in Mexico, his experience as minister of war, and his fame as a statesman seemed to point him out as the man ordained by Providence to be our leader. And now so soon distrusted! I tried to dismiss the whole thing from my mind, it distressed me so. But it would not down at my bidding. Many prominent men came to look after the troops of their respective States, sometimes in an official capacity, sometimes of their own accord. Among them was Thomas L. Clingman, of North Carolina, with whom I had a slight acquaintance. How it came about I quite forget, but we took a walk, one afternoon, down the Warrenton road, and fell to talking about the subject uppermost in my thoughts—Mr. Davis. Clingman seemed to know his character thoroughly, and fortified his opinions by facts of recent date at Montgomery and Richmond. Particulars need not be given, if, indeed, I could recall them; but the upshot of it all was, that in the opinion of many wise men the choice of Jefferson Davis as President of the Confederate States was a profound, perhaps a fatal, mistake. Unable to controvert a single position taken by Clingman, my heart sank low, and never fully rallied, for the sufficient reason that Mr. Davis’s career confirmed all that Clingman had said—all and more.

As the plot thickened, so did occurrences in and around head-quarters. Beauregard kept open house, as it were, many people dropping in to the several meals, some by invitation, others not. The fare was plain, wholesome, and abundant, rice cooked in South Carolina style being a favorite dish for breakfast as well as dinner. The new brigadiers also dropped in upon us from time to time. One of them was my old school-mate, Robert E. Rodes, a Lynchburger by birth, but now in command of Alabama troops. In him Beauregard had special confidence, giving him the front as McDowell approached. Rodes was killed in the valley in 1864, a general of division, full of promise, a man of ability, a first-rate soldier. Lynchburg has reason to be proud of two such men as Garland and Rodes. Soldiers continued to arrive. As fast as they came they were sent toward Bull Run, that being our line of defence. Some regiments excited general admiration by their fine personal appearance, their excellent equipment and soldierly bearing. None surpassed the First Virginia Regiment in neatness or in drill— in truth, few approached it. The poorest set as to size, looks, and dress were some of the South Carolinians. Louisiana sent a fine body of men. But by odds the best of our troops were the Texans. Gamer men never trod the earth. In their eyes and in their every movement they showed fight, and their career from first to last demonstrated the truth, in their case at least, of the old Latin adage, “Vidlus index est animi” — the face tells the character. I verily believe that fifty thousand Texans such as those who came to Virginia, properly handled, could whip any army the North could muster.

But as a whole our men did not compare with the Union soldiery. They were not so large of limb, so deep in the chest, or so firm-set, and in arms and clothing the comparison was still more damaging to the South. A friend of mine, who lingered in Washington till he could linger no longer, halted a day at Manassas on his way to his old home in Culpeper County. With great pride I called his attention to Hays’s magnificent Louisiana regiment, one thousand four hundred strong, drawn out full length at dress parade. He shook his head, sighed heavily, and described the stout-built, superbly equipped men he had seen pouring by thousands upon thousands down Pennsylvania Avenue. This incident made little impression on me at the time, my friend being of a despondent nature; but after my talk with Colonel Clingman it returned to me, and, I confess, depressed me not a little.

The camps were now deserted, the regiments being picketed on Bull Run. It was painful for me to go among the empty tents; it was like wandering about college in vacation – nay, worse, for it was morally certain that some, perhaps many, would return to the tents no more. I missed the faces of my friends; I longed for the lemonade “with a stick in it” that Captain Shields and Dr. Palmer used to give whenever I made them a visit, and I really pined for the red shirt and cheery voice of Captain H. Grey Latham, as he went from tent to tent, telling them new jokes, and on leaving, repeating his farewell formula, “Yours truly, John Dooly,” which actually got to be funny by perpetual repetition and became a by-word throughout the army. Finally I got so sick of the deserted camp that I asked Clifton Smith to let me share his pallet in the little shed-room cut off from the porch at head-quarters. He kindly assented, and I moved up, but still took my meals at camp. Doleful eating it would have been but for the occasional presence of my dear friend, Lieutenant Woodville Latham, who, being judge of a courtmartial then in session, had not yet joined the Eleventh Virginia at Bull Run.

The nights were so hot that I found it almost impossible to sleep in Clifton Smith’s little shed-room. My mind was excited by the approaching battle, and my habit of afternoon napping added to my sleeplessness. So the little sleep I got was in a chair on the porch. Near me, on the dinner-table, too long for any room in the house, lay young Goolsby, a lad of sixteen, who acted as night orderly. The calls upon him were so frequent and the pain of being awakened so great, that finally I said to him: “Sleep on, Goolsby, I’ll take your place.” He was very grateful. So I played night orderly from 12 o’clock till 6 A. M. thenceforward, and on that account slept the longer and the harder in the afternoon. Near sunset on the 18th I arose from Smith’s pallet in the shed-room, washed my face, and walked out upon the porch. It was filled with officers and men, all looking toward Bull Run. One of them said:

“That’s heavier firing than any I heard during the war in Mexico.”

“It was certainly very heavy,” was the reply, “but it seems to be over now.”

And that is all I know about the battle of the 18th. I had slept through the whole of it! Major Harrison, of our regiment, was killed; Colonel Moore, of the First Virginia Regiment, and Lieutenant James H. Lee, of the same regiment, were wounded, the latter seriously, as it turned out. There were no other casualties that particularly interested me.

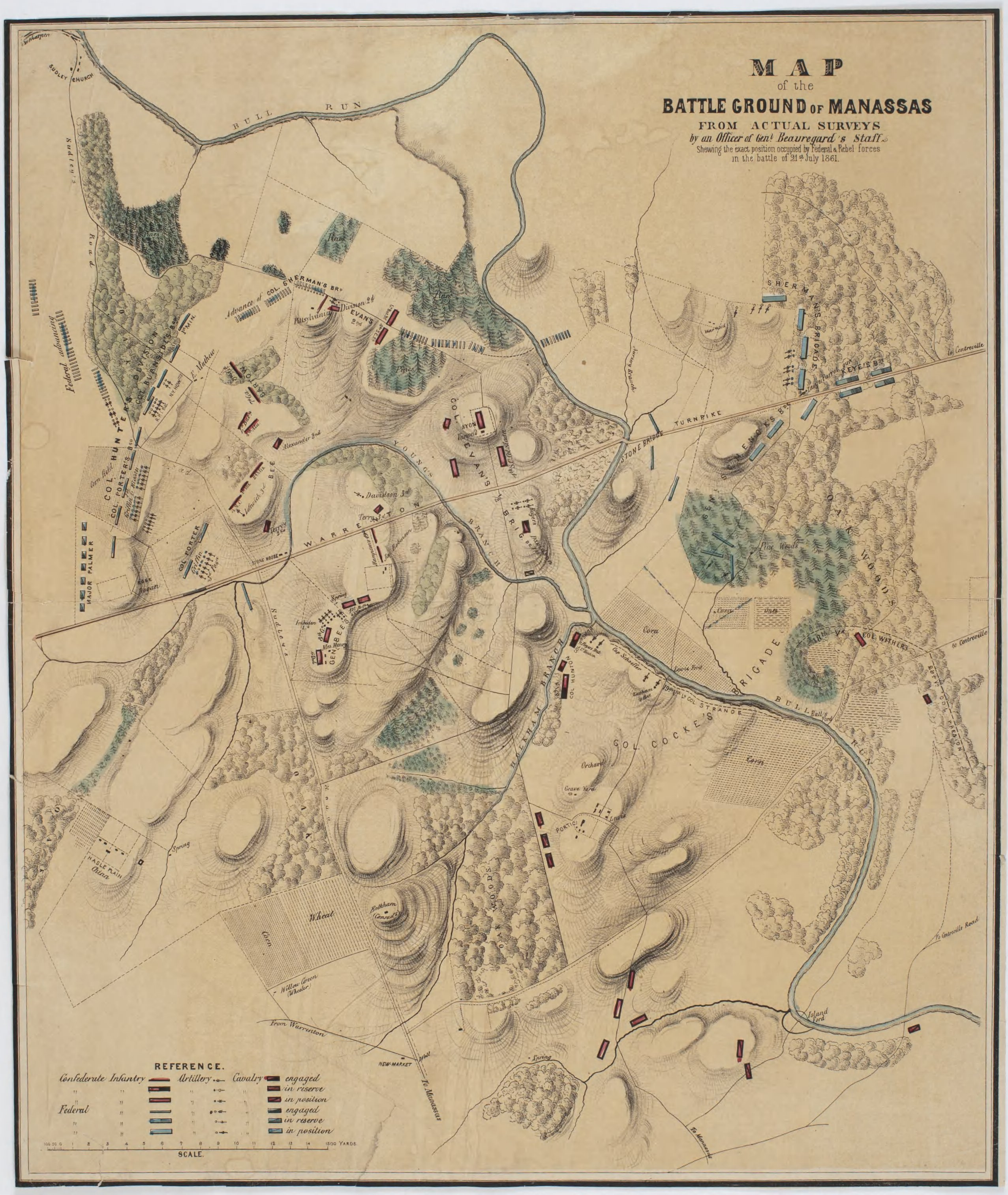

Every one knew the ordeal was at hand. The movements preceding the great tragedy had the hurry and convergence which belong to all catastrophes. A confused mixture of memories is left me – things relevant and irrelevant. L. W. Spratt, Thomas H. Wynne, Mrs. Bradley T. Johnson – the big guns of the intrenched camp; the night arrival of Johnston’s staff, the parting with my friend Latham – all these and many more recollections are piled up in my mind. Beauregard’s plan of battle had been approved by General Johnston. Ewell was to attack McDowell’s left at early dawn, flank him, and cut him off from Washington, our other brigades from left to right cooperating. Until midnight and later all of Colonel Jordan’s clerks were busy copying the battle orders, which were at once sent off to the divisions and brigades by couriers. I myself made many copies. The last sentence I remember to this day; it read as follows: “In case the enemy is defeated he is to be pursued by cavalry and artillery until he is driven across the Potomac.” He needed no pursuit, but went across the Potomac all the same. No, not all the same. Had we followed in force the result might have been different. I sat up as usual that night, but recall no event of interest.

As morning dawned, I wondered and wondered why no sound of battle was heard – none except the distant roar of Long Tom, which set the enemy in motion. How Ewell failed to get his order, how our plan of battle failed in consequence, and how near we came to defeat, is known to all. ‘Tis an old, and to Confederates, a sad story.

On the morning of the 18th, as Beauregard walked out to mount his horse, he stumbled and came near falling – a bad augury, which, we thought, brought a shadow over his face. But on this morning, the 21st all went well; the generals and their staffs, after an early breakfast, rode off in high spirits, victory in their very eyes. My duty was to look after the papers of the office, which had been hastily packed up, and, in case of danger, see that they were put on board a train, which was held in readiness to receive them and other valuable effects. The earth seemed to vomit men; they came in from all sides. Holmes, from Fredericksburg, at the head of his division, in a high-crown, very dusty beaver, I well recollect. He made me laugh. Barksdale, of Mississippi, halting his regiment to get ammunition. The militia ensconced behind the earthworks of the intrenched camp, their figures flit before me. It was a superb Sabbath day, cloudless, and at first not very hot. A sweet breeze from the west blew in my face as I stood on a hill overlooking the vale of Bull Run. I saw the enormous column of dust made by the enemy as they advanced upon our left. The field of battle evidently would be where the comet, then illuminating the skies, seemed to rest at night. Returning to head-quarters I reported to Colonel Jordan the movement upon our left.

“Has McDowell done that?” he asked, with animation. “Then Beauregard will give him all his old boots, for that is exactly where we want him.”

The colonel meant that Ewell would have a better chance of attack by reason of the weakening of McDowell’s left.

Again and again I walked out to watch the progress of the battle, which lasted a great deal longer than I expected or desired. The pictures of battles at a distance, in the English illustrated papers, give a good idea of what I saw, minus the stragglers and the wounded, who came out in increasing numbers as the day advanced, and disheartening President Davis as he rode out to the field in the afternoon. At noon or thereabout a report that our centre had been broken hurried me back to head-quarters, and although the report proved false, kept me there for several hours, the battle meanwhile raging fiercely, and not a sound from Ewell.

Restless and excited, I went into a neighboring house, occupied by a lone woman, who was in a peck of trouble about herself, her house, her everything. The bigger trouble outside filled my mind during the recital of her woes, so that I now recall none of them.

Unable longer to bear the suspense, I left important papers, etc., to take care of themselves, and set out for the battle-field, determined to go in and get rid of my fears and doubts by action. I reached the hill which I had so often visited in the morning, and paused awhile to look at some of our troops, who were rapidly moving from our right to our left. Just then – can I ever forget it? – there came, as it seemed, an instantaneous suppression of firing, and almost immediately a cheer went up and ran along the valley from end to end of our line. It meant victory – there was no mistaking the fact. I stood perfectly still, feeling no exultation whatever. An indescribable thankful sadness fell upon me, rooting me to the spot and plunging me into a deep reverie, which for a long time prevented me from seeing or hearing what went forward. Night had nearly fallen when I came to myself and started homeward. The road was filled with wounded men, their friends, and a few prisoners. I spoke kindly to the prisoners, and took in charge a badly wounded young man, carrying him to the hospital, from the back windows of which amputated legs and arms had already been thrown on the ground in a sickening pile.

At head-quarters there was a great crowd waiting for the generals and Mr. Davis to return. It was now quite dark. A deal of talking went on, but I observed little elation. People were worn out with excitement – too many had been killed – how many and who was yet to be learned. War is a sad business, even to the victors. I saw young George Burwell, fourteen years of age, bring in Colonel Corcoran, his personal captive.

I heard Colonel Porcher Miles’s withering retort to Congressman Ely, who tried to claim friendly acquaintance with him, but went off abashed in a linen duster with the other prisoners. I asked Colonel Preston what he thought of the day’s work.

“A glorious victory, which will produce immense results,” was his reply.

“When will we advance?” “We will be in Baltimore next week.” How far wrong even the wisest are? We never entered Baltimore, and that victorious army, rne-half of which had barely fired a shot, did not fight another pitched battle for nearly a year!

It was after midnight when I carried to the telegraph office Mr. Davis’s despatch announcing the victory. Inside the intrenched camp one thousand or twelve hundred prisoners were herded, the militia standing up side by side guarding them and forming a human picket-fence, funny to behold. It was clear as a bell when I walked back; the baleful comet hung over the field of battle; all was very still; I could almost hear the beating of my tired heart, that had gone through so much that day. Too much exhausted to play orderly, I slept in my chair like a top.

The next day, Monday, the 22d, it rained, a steady, straight downpour the livelong day. Everybody flocked to head-quarters. Not one word was said about a forward movement upon Washington. We had too many generals-in-chief; we were Southerners; we didn’t fancy marching in the mud and rain – we threw away a grand opportunity. For days, for weeks, you might say, our friends kept coming from Alexandria, saying with wonder and impatience: “Why don’t you come on? Why stay here doing nothing?” No sufficient answer, in my poor judgment, was ever given. The dead and the dying were forgotten in the general burst of congratulation. Now and then you would hear the loss of Bee and Bartow deplored, or of some individual friend it would be said: “Yes, he is gone, poor fellow”; but this was as nothing compared to the joyous hubbub over the victory. How proud and happy we were! Didn’t we know that we could whip the Yankees? Hadn’t we always said so? Henceforth it would be easy sailing – the war would soon be over, too soon for all the glory we felt sure of gaining. What fools!

Captain H. Grey Latham, in his red shirt, was a conspicuous figure at head-quarters. His battery had covered itself with renown; congratulations were showered upon him. I saw Captain (afterward colonel, on Lee’s staff) Henry E. Peyton come over from General Beauregard’s room blazing with excitement and exaltation. Yesterday he was a private – now he was a captain, promoted by Beauregard first of all because

of his signal gallantry on the field. “By – !” he exclaimed to me, “when I die, I intend to die gloriously.” Alas! Colonel Peyton, confidential clerk of the United States Senate and owner of one of the best farms in Loudoun County, is like to die in his bed as ingloriously as the rest of us.

A young Mr. Fauntleroy, desiring an interview with General Joseph E. Johnston, I offered to procure it for him, and pushed through the crowd to the table at which he sat. “Excuse me, General Johnston,” I began. “Excuse me, sir!” he replied, in tones that sent me away in a state of demoralization.

The next thing I remember is the coming on of night, and my resuming my post as night orderly. I was seldom aroused, and slept soundly in a chair, tilted back against the wall. In the yard just in front of me were a number of tents, one of which was occupied by President Davis. The rising sun awakened me. My eyes were still half open when Mr. Davis stepped out of his tent, in full dress, having made his toilet with care. Seeing no one but a private, apparently asleep in a chair, he looked about, turned, and slowly walked to the yard fence, on the other side of which a score or more of captured cannon were parked, Long Tom being conspicuous. The president stood and looked at the cannon for ten minutes or more. Having never seen him close at hand, I went up and looked at the cannon too, but in reality I was looking at him most intently.

That was the turning-point in my life. Had I gone up to him, made myself known, told him what I had done in his behalf, and asked something in return, my career in life would almost certainly have been far different. We were alone. It was an auspicious time to ask favors – just after a great victory – and he was very responsive to personal appeals. My prayer would have been heard. In that event I should have become a member of his political and military family, or, what would have suited me much better, have gone to London, as John R. Thompson afterward did, to pursue in the interest of the Confederacy my calling as a journalist. But Clingman’s talk had done its work. Already prejudiced against Mr. Davis, his face, as I examined it that fateful morning, lacked – or seemed to – the elements that might have overcome my prejudices. There was no magnetism in it – it did not draw me. Yet his voice was sweet, musical in a high degree, and that might have drawn me had I but spoken to him. I could not force myself to open my lips, but walked back to my chair on the open porch, and my lot in life was decided.

General Beauregard removed his head-quarters to the house of Mr. Ware, some distance from Manassas Station, a commodious brick building, in which our friend, Lieutenant James K. Lee, lay wounded. Mr. Ware’s family remained, but most of the house was given up to us. I slept in the garret with the soldier detailed to nurse Lieutenant Lee. In the yard were a number of tents occupied by the general and his staff. Colonel Jordan’s office was in the house. My duty, hitherto light and pleasant, now became somewhat heavy and disagreeable. I had to file and forward applications for furlough, based mainly upon surgeons’ certificates. This brought me in contact with many unlovely people, each anxious to have his case attended to at once. It was very worrying. Others beside myself, the clerks and staff officers, seemed to be as much worried by their labors as I was by mine. Fact is, young Southern gentlemen, used to having their own way, found it hard to be at the beck and call of anybody. The excitement of battle over, the detail of business was pure drudgery. We detested it.

The long, hot days of August dragged themselves away. No advance, no sign of it; the men in camp playing cards, the officers horse-racing. This disheartened me more than all things else, but I kept my thoughts to myself. At night I would walk out in the garden and brood over the possible result of this slow way of making war. The garden looked toward the battle-field. At times I thought I detected the odor of the carcasses, lightly buried there; at others I fancied I heard weird and doleful cries borne on the night wind. I grew melancholy.

Twice or thrice a day I went in to see Lieutenant Lee. Bright and hopeful of recovery, he gave his friends a cheery welcome and an invitation to share the abundant good things with which his mother and sisters kept him supplied. A visit to his sick chamber was literally a treat. The chances seemed all in his favor for two weeks or more after our arrival at the Ware house, but then there came a change for the worse, and soon the symptoms were such that his kinsman, Peachy R. Grattan. reporter of the court of appeals, was sent for. He rallied a little, but we saw the end was nigh. Mr. Grattan promised to send for me during the night in case anything happened, and at two o’clock I was called. The long respiration preceding death had set in. Mr. Grattan, kneeling at the bedside, was praying aloud. The prayer ended, he called the dying officer by name. “James” (louder), “James, is there anything you wish done?” Lieutenant Lee murmured an inarticulate response, made an apparent effort to remove the ring from the finger of his left hand, and sank back into the last slumber. I waited an hour in silence; still the long-drawn breathing kept up.

“No need to wait longer,” said Mr. Grattan; “he will not rouse any more.”

I went to my pallet in the garret, but could not sleep; at dawn I was down again. The long breathing continued; Mr. Grattan sat close to the head of the bed and I stood at the foot, my gaze fixed on the dying man’s face. Suddenly both his eyes opened wide; there was no “speculation” in them, but the whole room seemed flooded with their preternatural light. Just then the sun rose, and his eyes closed in everlasting darkness, to open, I doubt not, in everlasting day. So passed away the spirit of James K. Lee.

A furlough was given me to accompany the remains to Richmond, with indefinite leave of absence, there being no sign of active hostilities. In view of my infirm health a discharge was granted me after my arrival in Richmond, and thus ended the record of an unrenowned warrior.

Let me say a word or two in conclusion. In 1861 I was thirty-three years old; now I am fifty-five, gray and aged beyond my years by many afflictions. I wanted to see a great war, saw it, and pray God I may never see another. I recall what General Duff Green, an ardent Southerner, said in Washington, in the winter of 1861, to some hot-heads: “Anything, anything but war.” So said William C. Rives to some young men in Richmond just after the fall of Sumter: “Young gentlemen, you are eager for war—you little know what it is you are so anxious to see.” Those old men were right. War is simply horrible. The filth, the disease, the privation, the suffering, the mutilation, and, above all, the debasement of public and private morals, leave to war scarcely a redeeming feature.

The Old Virginia Gentleman: And Other Sketches, by George William Bagby

Hat Tip to John Hennessy

George W. Bagby bio

Dr. George W. Bagby at Findagrave.com

Recent Comments