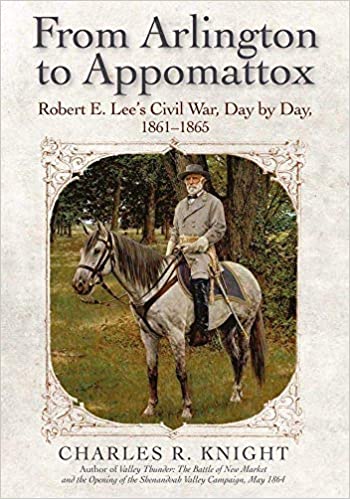

New from Savas Beatie is one of those volumes that Civil War researchers will keep on their reference shelves along with Warner, Heitman, Crute, Dyer, Boatner, Long, and Miers – Charles R. Knight’s From Arlington to Appomattox: Robert E. Lee’s Civil War Day by Day, 1861-1865. Mr. Knight has been good enough to answer a few questions about the book.

BR: You’ve spoken with us before – any updates with you?

CRK: Since our last interview, I’ve moved across the country…twice. First to the Civil War research hotbed of Phoenix, AZ, and then to the much better Raleigh, NC. Still in the museum field and now have 20+ years experience in the museums/historic sites field – a career choice I made for the money, obviously. Oh, and the family has grown by one since last time as well.

BR: In the beginning, this new book must have seemed either like an insurmountable task, or a put-my-nose-to-the-grindstone-and-it will-eventually-be-done procedural. What, in the first place, possessed you to undertake it? Were you influenced by Miers’s Lincoln Day-by-Day?

CRK: A number of years ago I was well into the research on my biography of “Little Billy” Mahone when Ted Savas sent me this cryptic message to call him. He asked me how that was going and said he had an idea that could use a lot of the same research materials, but looking at R.E. Lee rather than Mahone. “Go on,” I replied. He asked if I was familiar with E.B. Long’s CW Day by Day, which of course is an invaluable work looking at the major events of every day of the war. Ted explained that he wanted someone to do a similar work but focusing on Lee during the war. I thought “OK sure, how hard can this be? Between Lee’s own papers, the ORs, the writings of Lee’s major staff officers (Walter Taylor, Charles Marshall, Armistead Long) and D.S. Freeman to fill in the gaps, this shouldn’t be too much of an undertaking.” I cannot have been more wrong, that became apparent VERY quickly. For all the scores of titles that have been written in the last 160 years about Lee, no author – not even Freeman – set out to record the detail this type of project required. In fact the only person I am aware of for whom such a project had ever been attempted was Abraham Lincoln. The Lincoln Day by Day project was similar but quite different at the same time, in that it looked at his entire life and there was a team of researchers compiling EVERY known scrap of paper with Lincoln’s signature on it. This Lee project was concerned only with four years of his life, it was just me (although I could not have done it without the help of many friends and colleagues) pulling everything together, and I knew it would be an impossibility to even attempt to find everything. But I’m a detail person when it comes to research, and I found myself going down rabbit hole after rabbit hole, sometimes chasing things that wound up in the finished book, others that either hit a dead end or were not important enough to include.

BR: While nothing about this could have been easy, did you find any kind of freedom in the fact that you didn’t have to construct an overall narrative? Was there less “creative” writing?

CRK: With the exception of the introductory section for each month April 1861 through April 1865, it really was largely just compiling raw data: where Lee was, who he was with, who he wrote to, etc. There was no need to try to weave it into a sort of narrative for each day. That said, there are of course some days with gobs of information which do require a lot more organization than those for which there is little recorded. When I sat down to convert my notes into “complete” entries for each day, there were instances where I could move through several months in a matter of hours and other times where a single day of Lee’s life took me an entire weekend to do. Because of the lack of much interpretation, I was afraid that the finished product would be dry – and in some cases I admit it is – but, I think when you tackle large chunks, say at least a week at a time, you can really see how events both big and small take shape. And in a traditional biography that is lost.

BR: Cutting to the chase, what were some things you learned about the Marble Man that surprised you (individual events or overall characterizations)?

CRK: Without a doubt the most surprising revelations came from the private writings of those closest to Lee: either his family or his staff. Walter Taylor, Armistead Long, and others who were part of Lee’s inner circle wrote of their time with the General in the decades after his death, and the public by and large gobbled it up. But these were specifically designed for public eyes – none of them would say anything bad about their chief in that format. But when you look at their private letters – those not meant to be seen by the public at large – that is where you get their true thoughts. By reading Freeman one would never suspect that Lee harbored a tremendous temper and could hold a grudge for days on end, or that he would ever order his staff to fire on their own men. The writings of Lee’s military family however reveal much that would have made Freeman cringe. Taylor frequently griped about the lack of recognition he received from Lee and how frequently the General took out his temper on those around him at HQ. In fact Taylor referred to Lee in not so flattering terms as the “Tycoon.” Charles Venable – who butted heads with Lee perhaps more than any other of his aides – recorded some of the most eye opening details about Lee, and just how unpleasant life could be at ANV HQ. One of my favorite incidents I found that doesn’t come from one of the staff was an account by a gentleman who sat next to Lee on the train as the General returned to the army from a meeting in Richmond in the midst of the Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid, which noted how anxious Lee seemed and how distant he was whenever anyone tried to talk to him, and he was constantly looking out the windows on both sides of the car. No one at the time understood Lee’s behavior, but once they arrived at Gordonsville they all learned just how close they had come to being captured by Union horsemen and immediately grasped the reason for his odd actions. I was also surprised at how much things of a non-military nature Lee dealt with on an almost daily basis. When we look at battle or campaign studies, such things are often not mentioned or if they are it is just a cursory one. Personal tragedy struck Lee multiple times during the war, with the well-known death of his daughter Annie in the wake of Sharpsburg, but also the death of his two grandchildren – one during the Seven Days, and one only weeks after Annie’s death, the death of his daughter-in-law Charlotte the day after Christmas 1863, Rooney’s capture from his literal sick-bed days before Gettysburg, how much his wife’s nomadic lifestyle concerned him, and not to mention his own failing health.

BR: Can you describe how long it took to write the book, what the stumbling blocks were?

CRK: When I first began this project I was living in Norfolk, VA – hometown of Walter Taylor. So I had easy access to Taylor’s papers at the Norfolk Public Library and the important repositories in Richmond were only a couple hours away. Then I moved to Phoenix, which is of course widely known as one of the major centers of CW scholarship in the country. Access to original papers became quite difficult to say the least and an increasing amount of my research was done remotely. Then I really lucked out when I got a job in Raleigh and had the immense collections at UNC and Duke at my fingertips. The first six months I was in NC I spent almost every weekend in either Chapel Hill or Durham, and I found a lot of smaller collections that I may not have ever found otherwise, many of which had some excellent REL material. I was researching this for at least five years, and it took a good six months to convert the raw data in my notes into daily entries. I never intended to find EVERY piece of Lee correspondence or reference to him, and I know there are lots of them out there that I didn’t find, so there’s always that little voice in the back of your mind that wonders if one of them has info that would fill in some of the gaps.

BR: Can you describe your research and writing process? What online and brick and mortar sources did you rely on most?

CRK: I don’t remember now for certain, but I think the very first source I started with was Dowdey & Manarin’s volume of Lee’s papers. I just started a Word document and for every event in Lee’s life, be it a letter written or received, a meeting with someone, etc., I recorded it by date. When I was “done” I think that document was 600-something pages, and it still didn’t have all of my notes – some of which I just plugged directly into the manuscript. The first mss collection I targeted was Walter Taylor’s papers at the Norfolk Public Library. His wartime papers were published back in the mid-90s, but the original collection has so much more of value than just those – I learned a lot from Taylor’s post-war correspondence with the other members of Lee’s staff as well as other notable officers like Jed Hotchkiss and others; anybody who uses just the published letters misses out on so much that Taylor offers. I got to be on a first name basis with the folks at UNC, Duke, VA Historical Society (even though one archivist there just seemed to take a perverse delight in making me request Lee materials one letter a time), and the VA Library. And speaking of the Library of Virginia, they have some of Freeman’s original Lee notes – it is incredible to me what he was able to accomplish in a pre-internet world, in particular his list of Lee mentions in the Richmond newspapers. I much prefer hardcopy books to electronic versions, but in this instance I was very glad to be able to use the “search” function of the online version of the ORs. Thankfully I had been putting off the large multi-volume works – the ORs, Southern Historical Society Papers, Confederate Veteran – so my time in Arizona was not a complete waste research-wise, as I was able to tackle them either online or the actual books.

BR: How has the book been received so far?

CRK: I’ve heard nothing but good things. Well, except for one Amazon review from someone who didn’t seem to read the book description before purchasing.

BR: In the editorial process something always ends up on the cutting room floor so to speak. Was there anything in that didn’t make the final cut – things for which you expected to find support and came up dry, for example?

CRK: I was lucky in that regard, not much in the way of text was cut. The format of the book wasn’t really conducive to that – eliminate text and data rather than interpretation or fluff is gone. Some of the bios and explanatory text in the footnotes were trimmed, but nothing major. I had far more images than could be used, and thankfully Ted Savas likes images and uses far more than any other publisher but even still it was difficult to pick and choose what would make the cut.

BR: Were there any areas in which you found info lacking?

CRK: The first year of the war for Lee is probably the least documented part of his CW service. For this I blame Walter Taylor; well not Taylor himself, but his fiancée Bettie Saunders. Taylor served with Lee for all but the first 3 weeks of the war, joining the General as an aide in early May ’61. Taylor was a very observant and detail-oriented young man, and he wrote to Betty usually at least twice a week, more often when he could. His letters are the best source we have on the inner circle at ANV HQ. But his letters from the beginning of the war up until mid’62 don’t survive – Bettie for whatever reason destroyed them. When Taylor found this out he was not happy and he pleaded with her to save them, as he was writing not only for her information, but for his own use as well – his letters to her were the only personal record he was keeping of his service. When he wrote his two books in later years, one can plainly see he was referring back to those letters as his main source. So without Taylor’s insight for Lee’s time as commander of Virginia’s military forces the first few months of 1861, his time in the mountains of western Virginia that summer and autumn, and while in command on the south Atlantic coast in late 61 and early 62, the sources are largely few and far between. And whenever Taylor went on leave later, documentation of HQ suffered as a result. A couple other areas were surprisingly little-documented as well: the period after Sharpsburg, as well as winter encampments.

BR: What’s next for you?

CRK: I hope to have my Billy Mahone manuscript finished by the end of the year, assuming of course places open back up for outside researchers. Mahone’s papers – almost 500 boxes of them – are at Duke, which as of now, is still closed to non-Duke people. Mahone is one of the few remaining important figures of the ANV without a good biography. Nelson Blake did a bio of Little Billy back in the 30s, but he focused on Mahone’s post-war political and railroad career – he devoted only about 25 pages to the Civil War. As one of the most peculiar of Lee’s lieutenants, Mahone clearly deserves better. Once that is done, I want to publish Charles Venable’s memoirs and letters. His writings are a great resource on Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia and only a relative handful of folks are aware of them and even fewer have ever used them.

Recent Comments