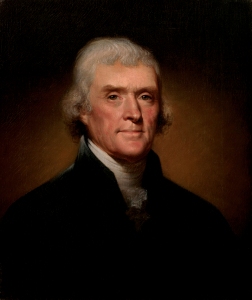

Much has been said about the notion of States’ Rights as the cause of the Civil War from a Confederate perspective, and of the idea of the United States formed under its Constitution as a sort of “men’s club,” with a membership consisting of states who were free to come and go as they pleased. Is the near absence from the The Federalist of the concept of secession due to a general assumption of applicability or of irrelevance, even of inconceivability? I’m no Constitutional scholar, but I thought you all might like to read these paragraphs from Ron Chernow’s Alexander Hamilton, which can be found on pages 573-574. Thomas Jefferson was a real piece of work, man. A real gem – who, if you recall, was not a framer of the Constitution. We pick up the story in 1798 (ten years after the Constitution’s ratification), after the passage of the Federalist’s onerous Alien and Sedition Acts [brackets and emphasis mine]:

Alexander Hamilton – chief architect of the Constitution, but backer of the Alien and Sedition Acts as a private citizen

Many Republicans thought it best to sit back and let the Federalists blow themselves up. As [James] Monroe put it, the more the Federalist party was “left to itself, the sooner will its ruin follow.” Jefferson and [James] Madison were not that patient, especially after Hamilton became inspector general of the new army. Jefferson thought the Republicans had a duty to stop the Sedition Act, explaining later that he considered that law “to be nullity as absolute and as palpable as if Congress had ordered us to fall down and worship a golden image.” With Federalists in control of the government, the political magician decided that he and Madison would draft resolutions for two state legislatures, declaring the Alien and Sedition Acts to be unconstitutional. The two men operated by stealth and kept their authorship anonymous to create the illusion of a groundswell of popular opposition. Jefferson drafted his resolution for the Kentucky legislature and Madison for Virginia. The Kentucky Resolutions passed on November 16, 1798, and the Virginia Resolutions on December 24. Jefferson’s biographer Dumas Malone has noted that the vice president [Jefferson, serving under Federalist John Adams] could have been brought up on sedition charges, possibly even impeached for treason, had his actions been uncovered at the time.

James Madison did a complete 180 on the relation of state and federal law, when it suited him politically

In writing the Kentucky Resolutions, Jefferson turned to language that even Madison found excessive. Of the Alien and Sedition Acts, he warned that “unless arrested at the threshold,” they would “necessarily drive these states into revolution and blood.” He wasn’t calling for peaceful protests or civil disobedience: he was calling for outright rebellion, against the federal government of which he was vice president. In editing Jefferson’s words, the Kentucky legislature deleted his call for ‘nullification” of laws that violated states’ rights. The more moderate Madison said that the states, in contesting obnoxious laws, should “interpose for arresting the progress of evil.” This was a breathtaking evolution for a man who had pleaded at the Constitutional Convention that the federal government should possess a veto over state laws. In the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, Jefferson and Madison set forth a radical doctrine of States’ Rights that effectively undermined the Constitution.

Neither Jefferson nor Madison sensed that they had sponsored measures as inimical as the Alien and Sedition Acts themselves. “Their nullification effort, if others had picked it up, would have been a greater threat than the misguided {alien and sedition} laws, which were soon rendered feckless by ridicule and electoral pressure,” Garry Wills has written. The theoretical damage of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions was deep and lasting. Hamilton and others had argued that the Constitution transcended state governments and directly expressed the will of the American people. Hence, the Constitution began “We the People of the United States” and was ratified by special conventions, not state legislatures. Now Jefferson and Madison lent their imprimatur to an outmoded theory in which the Constitution became a compact of the states, not of their citizens. By this logic, states could refrain from federal legislation they considered unconstitutional. This was a clear recipe for calamitous dissension and ultimate disunion. George Washington was so appalled by the Virginia Resolutions that he told Patrick Henry that if “systematically and pertinaciously pursued,” they would “dissolve the union or produce coercion.” The influence of the doctrine of states’ rights, especially in the version promulgated by Jefferson, reverberated right up to the Civil War and beyond. At the close of the war, James Garfield of Ohio, the future president, wrote that the Kentucky Resolutions “contained the germ of nullification and secession, and we are today reaping its fruits.”

I have never been a huge fan of Jefferson. He is brilliant, but in many ways, also a brilliant failure. He was an erratic politician, with more downsides than up, IMO.

I’m a bigger fan of James A. Garfield.:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

TJ reminds me of Apollo in that Star Trek episode. They both were desirous of an agrarian society in a time-locked, sealed vacuum. With strict aristocratic societies where everyone knows their place, and with them, of course, at the top, and aloof.

LikeLike